Part 1: The Basics of Economics

Section 1: What is Economics?

1.1 Defining Economics: The Study of Scarcity and Choice

Let’s start with the most basic question: What is Economics?

Think about it this way. As human beings, our wants are unlimited. We want a good phone, a nice house, a car, fancy clothes, holidays, and so on. The list never ends.

However, the resources to get these things are limited. Resources mean things like money, time, land, raw materials (like wood or iron), and people to do the work (labour). Because these resources are limited, we face a problem called scarcity.

Scarcity is the basic problem of life and economics. It simply means that we don’t have enough of everything to satisfy everyone’s wants.

Because of scarcity, we are forced to make choices.

- Example: Imagine you have ₹100. You want to watch a movie (which costs ₹100) and also buy a book (which costs ₹100). You cannot do both because your resource (money) is limited to ₹100. You have to choose one: either the movie or the book.

Economics is the study of how people make these choices. It studies how we (as individuals), how families, companies, and even the government use our limited resources to satisfy our unlimited wants in the best possible way.

So, in simple words, Economics is the science of making choices when there is scarcity. It deals with three main activities:

- Production: How goods are made (e.g., how a factory builds a car).

- Distribution: How these goods reach the people (e.g., how the car gets from the factory to a showroom near your house).

- Consumption: How people use these goods (e.g., you buying and driving the car).

1.2 The Two Main Branches: Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

Economics is a very big subject, so to make it easier to study, we divide it into two main parts: Microeconomics and Macroeconomics.

Think of them as two different ways of looking at the same thing. They are deeply connected and work together.

Let’s use an analogy: Imagine a huge forest.

- Microeconomics is like studying a single tree in that forest. You look at its leaves, its branches, its roots, and the insects living on it. You are focusing on one individual unit.

- Macroeconomics is like climbing a mountain and looking at the entire forest. You are not looking at individual trees. Instead, you are looking at the health of the whole forest, whether it is growing or shrinking, and the overall climate affecting it.

Now, let’s look at them in more detail.

1.2.1 Microeconomics: Looking at the Small Picture (Bottom-Up View)

What it is: Microeconomics studies the economic decisions and behaviour of individual units. This means it looks at:

- An individual person or a single family (a household).

- A single company or a firm.

- A specific market (like the market for smartphones in India).

It’s a “bottom-up” view because it starts with the smallest parts and builds up. It tries to understand how these small units make decisions. For example, why do you decide to buy a Samsung phone instead of an Apple phone? Or, how does a company like Tata Motors decide the price of its cars?

Key Ideas in Microeconomics:

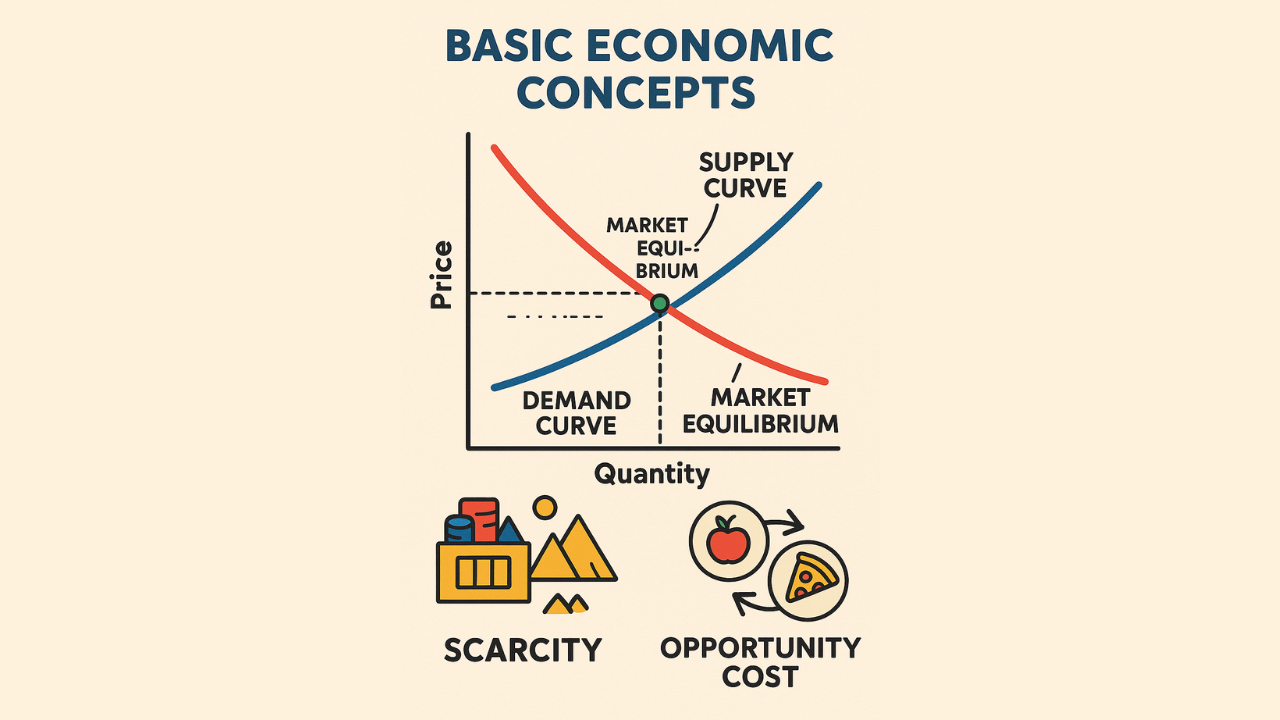

- Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium: This is the most important idea in microeconomics.

- Demand: How much of a product people are willing to buy at a certain price. (If mangoes are cheap, demand is high. If they are very expensive, demand is low).

- Supply: How much of a product sellers are willing to sell at a certain price. (If the price of mangoes is high, farmers will want to sell more).

- Equilibrium: This is the “sweet spot” or the balance point. It’s the price where the amount buyers want to buy is exactly equal to the amount sellers want to sell. This is how prices are decided in a market.

- Production Theory: This studies how companies turn inputs (like steel, plastic, and workers) into outputs (like a finished car). It looks at how they can do this in the most efficient and cheapest way.

- Costs of Production: This idea says that the price of any product is decided by how much money was spent to make it. A company needs to know its costs to set the right price and make a profit.

- Labor Economics: This focuses only on the job market. It looks at how salaries (wages) are decided, why some people are unemployed, and the relationship between workers and employers.

Why is this important for UPSC?

As a civil servant, you will be making policies that affect individual people and businesses. Microeconomics helps you understand the real-world impact of these policies.

- Example 1: The government sets a Minimum Support Price (MSP) for wheat. Using microeconomics, you can understand how this will affect a single farmer’s income, the price of bread for a consumer, and whether it will lead to food price inflation.

- Example 2: The government puts a new tax on cigarettes. Microeconomics helps you predict how this will change the behaviour of individual smokers and the business of cigarette companies.

1.2.2 Macroeconomics: Looking at the Big Picture (Top-Down View)

What it is: Macroeconomics studies the economy as a whole. It doesn’t care about one person or one company. It looks at the big picture for the entire country or even the world.

It is a “top-down” view. It asks big questions like:

- Is the Indian economy growing or slowing down?

- Why are prices of everything rising in the country (inflation)?

- Why are so many people unemployed?

- How can we reduce poverty in the whole country?

It deals with big, national issues and uses “aggregate” data, which means total data. For example, it looks at:

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP): The total value of all goods and services produced in a country in a year.

- National Income: The total income of everyone in the country.

- Inflation: The rate at which the general level of prices is rising.

- Unemployment: The number of people who want to work but don’t have jobs.

Who started it and what are its tools?

A famous economist, John Maynard Keynes, is known as the father of modern macroeconomics. He argued that during bad times like the Great Depression of the 1930s, the government must step in and spend money to manage the economy.

The main tools of macroeconomics are:

- Aggregate Demand: The total demand for all goods and services from all people in the entire country.

- Aggregate Supply: The total supply of all goods and services from all producers in the entire country.

Why is this important for UPSC?

Macroeconomics is extremely important for the UPSC exam, especially for General Studies Paper 3. This is the language spoken by the government and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

- Understanding macroeconomics helps you understand the Union Budget. Why is the government spending more on roads? Why are taxes being increased or decreased?

- It helps you understand the RBI’s monetary policy. Why did the RBI increase interest rates? How does this control inflation?

- It helps you understand the logic behind big government schemes aimed at increasing economic growth and creating jobs.

1.2.3 How Micro and Macro are Connected

Although they look at things differently, micro and macroeconomics are not separate. They are two sides of the same coin and are deeply connected.

The big picture (macro) is made up of many small pictures (micro).

- For example, the overall inflation rate in India (a macro issue) is just the average of the price changes of millions of individual products like dal, petrol, soap, and mobile recharges (micro things).

- Similarly, the total savings of India (a macro number) is simply the sum of the savings of every single household and company in the country (micro units).

This connection is very important for policy-making.

A big government policy (macro) will only work if it successfully influences the decisions of small, individual players (micro).

- Example: The government launched the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme. This is a big macro policy to boost manufacturing in India. The goal is to increase India’s GDP and exports (macro goals).

- However, this scheme will only succeed if an individual company (micro unit) decides that the government’s incentive is good enough for it to invest crores of rupees in a new factory. The success of the big macro policy depends entirely on millions of such individual micro decisions.

Similarly, big macro problems often start from small micro issues.

- Example: High food inflation in India (a macro problem) is often caused by micro problems. For instance, if heavy rains destroy the onion crop in Maharashtra (a micro event), the supply of onions across the country will fall, and its price will shoot up, contributing to the overall macro inflation.

For a civil servant, this means you need a ‘dual-lens’ approach. You need to be able to zoom in to see the individual tree (micro) and also zoom out to see the whole forest (macro) to understand any economic issue properly and create effective policies.

Section 2: The Main Problem in Economics

2.1 Scarcity: The Problem Everyone Faces

As we discussed before, the single most important idea in all of economics is scarcity.

Scarcity is the simple fact that we cannot have everything we want. Why? Because our wants for things (goods and services) are far greater than what can be produced with our limited resources. It’s the universal problem of having unlimited wants but living in a world of limited resources. This is the fundamental economic problem for every person, every family, and every country.

Needs vs. Wants 🤔

To understand scarcity better, let’s see the difference between needs and wants.

- Needs are things that are absolutely essential for you to survive. This includes basic food, clean water, and a place to live (shelter). Needs are limited; you can only eat so much food or live in one house at a time.

- Wants are all the other things you desire to make your life more comfortable, fun, or enjoyable. This could be a smartphone, a Netflix subscription, a car, or a holiday in Goa. Wants are infinite. As soon as you get one thing, you start wanting something else.

This endless cycle of wants is what creates the problem of scarcity when faced with our limited resources.

Are all goods scarce?

No, but most are. A good that is not scarce is called a free good. This is something you can use without stopping someone else from using it. The best example is gravity. Your use of gravity doesn’t reduce the amount of gravity available for others.

However, most things we think of as “free” are actually scarce. Let’s take air. It seems free and abundant, right? But air has alternative uses. We need it to breathe clean, healthy air. But factories and cars use it as a place to dump their pollution. So, we have a choice: should we use the air for breathing or for dumping waste? The more we pollute (one choice), the less healthy the air is to breathe (giving up the other choice). Because we have to make a choice or a trade-off, even air is considered a scarce good in economics.

2.2 The Three Central Questions of an Economy

The reality of scarcity forces every single society—whether it’s India, the USA, or a small village—to answer three basic and very important questions.

- What to produce? 🧐 Since we can’t produce everything, we must decide what things to make and in how much quantity. Our resources are limited. If the government decides to use steel and money to build more tanks and military weapons, it means there will be less steel and money available to build new schools or hospitals. A society has to make a choice.

- How to produce? ⚙️ After deciding what to make, a society must decide the method of production. For example, should we make clothes using many workers (this is called labour-intensive production) or by using big, expensive machines (called capital-intensive production)? Should we build water pipes using copper or plastic? The goal is to choose the most efficient method that uses our scarce resources in the best possible way.

- For whom to produce? 👨👩👧👦 Once the goods and services are made, how do we distribute them among the people? Who gets what? Should the person who can pay the most get the product? Or should it be given based on who needs it the most? For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, should the limited supply of vaccines go to the rich first, or to the elderly and frontline workers? This question is all about sharing the country’s total output and deals with big ideas like fairness, equality, and justice.

2.3 Factors of Production

The scarce resources that are used to make all goods and services are called Factors of Production. Think of them as the basic ingredients of an economy. There are four main types:

- Land 🏞️ This doesn’t just mean the physical ground. In economics, ‘Land’ includes all natural resources. This means things like minerals (iron ore, coal), forests, rivers, oil, and sunshine. A country’s economy is often shaped by the natural resources it has.

- Labour 💪 This is the human effort—both physical and mental—that goes into producing something. It’s the work done by a farmer in the field, an engineer designing a bridge, or a teacher in a classroom. The quality of labour is very important. When workers are well-educated, skilled, and healthy, we call it good human capital. A country with good human capital can produce more things more efficiently.

- Capital 🏭 This is a tricky one. In everyday language, we think of capital as money. But in economics, Capital means man-made goods that are used to produce other goods. It refers to physical assets like machinery, tools, factories, computers, roads, and bridges. Money itself doesn’t produce anything; you can’t build a chair with a ₹500 note. But you can use money to buy a machine (which is a capital good) that can then be used to produce thousands of chairs.

- Enterprise (or Entrepreneurship) 💡 This is the special human skill that brings the other three factors (land, labour, capital) together to produce something. The person who does this is called an entrepreneur. An entrepreneur is a risk-taker who has a business idea, organises the resources, and makes all the important decisions. People like Ratan Tata, or even a local person who starts a small shop, are entrepreneurs. If their business is successful, their reward is profit.

2.4 Opportunity Cost: The Real Cost of Every Choice

This is one of the most important concepts in economics. Because scarcity forces us to choose, every choice we make has a hidden cost.

Definition: Opportunity Cost is the value of the next-best alternative that you have to give up when you make a choice. It’s not the value of all the things you gave up, just the single best one.

There is a great saying: “Choosing is refusing.” When you choose one thing, you are refusing the benefit of the next best thing.

Let’s look at some simple examples:

- Individual Level: Suppose you have a free evening. You can either watch a movie or study for your exam. You choose to watch the movie. The opportunity cost of watching the movie is the studying you gave up.

- College Example: A student decides to study for a 4-year engineering degree. The cost is not just the college fees (say, ₹8 lakhs). The bigger, hidden cost is the salary she could have earned by working a job for those four years (say, ₹12 lakhs). This lost income of ₹12 lakhs is the opportunity cost of her degree.

- Business Level: A farmer has a piece of land. He can either plant wheat or corn. He chooses to plant wheat. The opportunity cost of planting wheat is the profit he could have earned from planting corn.

- Government Level: A city has a budget of ₹1 crore. It can either repair 1 km of road OR build 2 km of new bicycle paths. If the government chooses to repair the road, the opportunity cost is not ₹1 crore. The real opportunity cost is the 2 km of bicycle paths that could not be built.

Why this is SUPER IMPORTANT for UPSC

The Union Budget of India is the biggest example of managing opportunity costs.

- Recently, the government has decided to spend a huge amount of money on Capital Expenditure (Capex)—this means building long-term assets like highways, railways, and ports. This is great for the country’s future growth.

- But here’s the trade-off. The money used for building a highway is money that cannot be used for something else right now. This “something else” is the opportunity cost.

- What is the opportunity cost of building a new expressway? It is the benefit we give up from not spending that money on other things, such as:

- Hiring more doctors and teachers.

- Giving more money to schemes for child nutrition.

- Providing higher subsidies to poor farmers.

When you write an answer in the UPSC Mains exam, using the concept of opportunity cost makes your answer much more analytical and intelligent. Instead of just listing the pros and cons of a government policy, you can say:

“While the government’s focus on capital expenditure is beneficial for long-term growth, it comes with a significant opportunity cost. The marginal benefit of building one more kilometre of road must be carefully weighed against the marginal opportunity cost of not being able to fund, for example, a certain number of new primary health centres in villages.”

This shows the examiner that you understand the deep economic trade-offs that the government has to make.

Section 3: How Markets Work: Demand, Supply, and Balance

The meeting place for buyers and sellers is a market. It could be your local vegetable market or the Indian stock market. The prices of things in any market are decided by two powerful forces: Demand and Supply. Understanding these two is key to understanding a market economy.

3.1 The Law of Demand

This law explains the behaviour of buyers (consumers).

What it is: The Law of Demand is a very simple idea. It says that if all other things remain the same, when the price of a good goes up 🔼, people will want to buy less of it 🔽. And, when the price of a good goes down 🔽, people will want to buy more of it 🔼.

This is an inverse relationship (they move in opposite directions). Why does this happen? Because our money is limited. If the price of onions shoots up to ₹100 per kg, our purchasing power is reduced, and we are forced to buy less. If the price drops to ₹20 per kg, we might buy more.

For demand to be real (effective demand), you must have both the desire to buy something and the ability (money) to pay for it.

The Demand Curve

A demand curve is just a picture (a graph) of this law. It’s a line that slopes downwards from left to right, showing that as the price falls, the quantity people demand increases.

What causes demand to change?

A change in the price of a product makes us move up or down along the same demand curve. But sometimes, people start wanting more or less of a product even if the price hasn’t changed. This causes the entire demand curve to shift to the left (demand decreases) or to the right (demand increases). The reasons for this shift are called the determinants of demand.

Here are the main ones:

- Income of Consumers:

- Normal Goods: For most things, when your income increases, you demand more of them. If you get a promotion, you might buy more branded clothes. These are normal goods.

- Inferior Goods: For some things, when your income increases, you demand less. If you get richer, you might stop travelling by city bus and buy a bike instead. Here, bus travel is an inferior good.

- Prices of Related Goods:

- Substitutes: These are goods you can use in place of each other, like tea and coffee. If the price of coffee suddenly becomes very high, many people will switch to drinking tea. So, a price increase for coffee leads to an increase in demand for tea.

- Complements: These are goods that are used together, like a car and petrol. If the price of petrol goes up a lot, people might decide not to buy a car. So, a price increase for petrol leads to a decrease in demand for cars.

- Tastes and Preferences: Demand changes with fashion, trends, and health awareness. If a famous cricketer advertises a health drink, its demand might suddenly increase.

- Consumer Expectations: If you expect the price of something to rise in the future, you will buy more of it now. If you hear that smartphone prices will increase next month because of a new tax, you might rush to buy one today.

- Size of Population: More people means more demand. As a city’s population grows, the demand for houses, food, and water naturally increases.

Exception to the Law: Giffen Goods

In very rare cases, the law of demand doesn’t work. This happens with Giffen goods. A Giffen good is a very basic, low-quality food (like a coarse grain like bajra for a very poor family) that makes up a large part of their diet.

- Example: Imagine a poor labourer eats only bajra and a little bit of dal every day. If the price of bajra increases, he becomes even poorer. He can no longer afford to buy even that small amount of dal. To avoid starving, he is forced to stop buying dal and use that money to buy more bajra to fill his stomach.

- Here, an increase in price led to an increase in demand. This is a very rare exception.

3.2 The Law of Supply

This law explains the behaviour of sellers (producers).

What it is: The Law of Supply is the opposite of the law of demand. It says that when the price of a good goes up 🔼, producers will want to sell more of it 🔼. And, when the price of a good goes down 🔽, producers will want to sell less of it 🔽.

This is a direct relationship (they move in the same direction). Why? Because producers are in business to make a profit. Higher prices mean higher potential profits, which gives them a bigger incentive to produce and sell more.

The Supply Curve

The supply curve is a graph that shows this relationship. It’s a line that slopes upwards from left to right, showing that producers are willing to supply more at higher prices.

What causes supply to change?

Just like with demand, factors other than the price can cause the entire supply curve to shift. These are the determinants of supply.

- Price of Resources (Input Costs): If the cost of raw materials goes up, production becomes more expensive and less profitable. For example, if the price of cotton increases, a T-shirt company will produce fewer T-shirts. This decreases supply.

- Technological Advancements: A new machine that can produce goods faster or cheaper will increase supply. For example, a new printing press that uses less ink and paper will encourage a publisher to supply more books.

- Taxes and Subsidies: If the government puts a high tax on producing a good, it increases the cost and reduces supply. If the government gives a subsidy (a financial help), it lowers the cost and increases supply. For example, a subsidy on solar panels encourages companies to produce more of them.

- Number of Firms: If more companies enter a market, the total supply will increase.

3.3 Market Equilibrium

This is the point where the two forces of demand and supply meet and balance each other.

What it is: Equilibrium is the situation where the price has reached a level where the quantity demanded is exactly equal to the quantity supplied. This price is called the equilibrium price or the market-clearing price.

At this point, every buyer who wants to buy at that price finds a seller, and every seller who wants to sell at that price finds a buyer. There is no shortage and no surplus. The market is in balance.

How Equilibrium Changes

The market equilibrium can change. If any of the “determinants” we discussed earlier changes, one of the curves will shift, and a new equilibrium point will be created.

- Example: Suppose a report comes out saying mangoes are very good for health. This will increase the demand for mangoes (the demand curve shifts to the right). At the old price, there will now be a shortage of mangoes. This shortage will push the price up until a new, higher equilibrium price is reached, where demand once again equals supply.

3.4 Elasticity: Measuring Sensitivity

Elasticity is a very important concept that measures how sensitive one thing is to a change in another. It basically asks the question: “If I change X by a little bit, how much will Y change?”

Price Elasticity of Demand (PED)

This is the most common type. It measures how much the quantity demanded changes when the price changes.

- Elastic Demand (Sensitive): Here, a small change in price leads to a big change in demand. This is common for luxury goods or goods with many substitutes. For example, if the price of a specific brand of chocolate goes up by 10%, people might easily switch to another brand, causing demand for the first brand to fall by 30%.

- Inelastic Demand (Not Sensitive): Here, even a big change in price causes only a small change in demand. This is true for necessities like salt, life-saving medicines, or petrol. If the price of petrol goes up by 20%, you might try to drive a little less, but you still need it, so your demand might fall by only 5%.

Other Types of Elasticity

- Income Elasticity: Measures how demand changes when your income changes. It tells us if a good is a normal good or an inferior good.

- Cross Elasticity: Measures how the demand for Good A changes when the price of Good B changes. It tells us if goods are substitutes (positive elasticity) or complements (negative elasticity).

Why is Elasticity SUPER IMPORTANT for UPSC?

The government uses the concept of elasticity every day to make policies. It is the practical foundation for many decisions.

- Goods and Services Tax (GST): The GST structure is a perfect example of elasticity.

- Essentials like salt and unpackaged food have inelastic demand. People have to buy them no matter the price. Taxing them heavily would hurt the poor a lot. That’s why they are in the 0% or 5% GST slab.

- Luxury items like expensive cars or ‘sin’ goods like tobacco have more elastic demand. The government taxes them at the highest rate (28%). This helps raise more revenue from those who can afford it without hurting the poor.

- Minimum Support Price (MSP): When the government sets an MSP for a crop like wheat, it is setting a price floor. The financial cost of this policy (how much surplus grain the government has to buy) depends heavily on the elasticity of demand and supply for wheat. If demand is very inelastic, consumers will keep buying even at a higher price, and the government’s burden will be less.

Section 4: Market Structures and Competition

First, what is a market structure? In simple words, it’s just a way to classify or categorise different industries based on how much competition exists in them.

The structure of a market is very important because it affects how companies in that market behave. It decides things like: How do they set prices? How much do they produce? How much profit can they make?

We can classify any market by looking at a few key things:

- How many buyers and sellers are there?

- Are the products sold by different companies identical or are they different from each other?

- Is it easy or difficult for a new company to enter that market? (We call this barriers to entry).

Markets can range from having intense competition to having no competition at all. Let’s look at the main types.

4.1 Perfect Competition

Think of this as an ideal, “perfect” situation which is used as a benchmark in economics. It’s rare to find it in the real world in its pure form.

What are its features? 🌟

- Many Buyers and Sellers: There are thousands of sellers and thousands of buyers. Because there are so many, no single person or company is big enough to influence the price.

- Homogeneous Product: “Homogeneous” means identical. All companies sell the exact same product. There is no difference in quality, size, or branding.

- Free Entry and Exit: It is very easy for a new company to start selling in this market, and it’s also very easy for an existing company to leave. There are no major hurdles like needing a big investment or a special government license.

- Perfect Information: All buyers and sellers know everything. They know all the prices being charged and the quality of the product.

- Price Takers: Because of all the above reasons, individual companies have zero control over the price. They have to accept the market price that is decided by the total demand and supply. They are “price takers,” not price makers.

What is the result?

This is the best-case scenario for consumers. Competition is so intense that prices are pushed down to the lowest possible level, and companies are forced to be super-efficient. In the long run, companies in this market only make “normal profits”—just enough money to stay in business, but not huge excess profits.

Examples in India: While no market is truly “perfect,” some come close.

- A local vegetable mandi: Imagine a market where hundreds of farmers are selling the same type of potato. The potatoes are identical, and no single farmer can charge a higher price than the market rate.

- The stock market: Millions of people are buying and selling shares of a company like Reliance. The shares are identical, and no single buyer or seller can control the share price.

4.2 Monopoly

This is the exact opposite of perfect competition. “Mono” means single.

What are its features? 👑

- Single Seller: There is only one company that produces and sells the entire product.

- No Close Substitutes: Consumers have no other good alternative to buy. If you don’t buy from the monopolist, you don’t get the product at all.

- High Barriers to Entry: It is extremely difficult or impossible for other companies to enter the market. This could be because:

- The startup cost is too high (e.g., building a whole railway network).

- The company owns a patent or special technology.

- The government has given an exclusive license to only one company.

- Price Maker: The monopolist has significant control over the price of the product. They can decide what price to charge.

What is the result?

A monopoly is generally bad for consumers. Without any competition, the monopolist will usually produce less quantity and sell it at a higher price to maximise its profit. This reduces consumer welfare. Also, with no competition, there is very little pressure on the company to innovate or improve its quality.

Examples in India:

- Indian Railways: For its network operations (the tracks, signals etc.), it is a monopoly. You cannot choose to travel on another company’s railway tracks in India.

- Natural Monopolies: In some sectors, it is most efficient for only one firm to operate because the initial setup costs are massive. For example, it would be wasteful for three different companies to lay their own separate water pipelines to your house. So, local water supply and electricity distribution grids are often natural monopolies.

4.3 Monopolistic Competition

This is a very realistic and common market structure that is a mix of both monopoly and competition.

What are its features? 🛍️

- Large Number of Firms: There are many companies competing with each other.

- Product Differentiation: This is the most important feature. All companies sell products that are similar but not identical. They try to make their product seem different from their competitors. This difference can be created through:

- Branding (e.g., Nike vs. Adidas)

- Packaging

- Quality or Design

- Free Entry and Exit: It’s relatively easy for new firms to enter the market.

- Non-Price Competition: Companies don’t just compete on price. They compete heavily through advertising, marketing, and building brand loyalty.

What is the result?

Because each company has a slightly different product (like a unique brand of soap), it has a small amount of monopoly power and some control over its price. However, because there are many other competitors, this power is limited. If they raise their price too much, customers will switch to another brand. Like perfect competition, firms here also only make normal profits in the long run. The best thing for consumers is the wide variety of choices.

Examples in India: This market structure is everywhere!

- Restaurants: Many restaurants, but each offers a different menu, ambiance, or brand.

- Clothing and Shoe brands: So many brands, each with its own style and identity.

- Salons, Hotels, and everyday FMCG products like soaps and toothpastes.

4.4 Oligopoly

“Oligo” means few. This is a market that is controlled by a few very large firms.

What are its features? 📲

- Few Dominant Firms: A small number of companies (e.g., 3 to 5) control the majority of the market.

- High Barriers to Entry: It is very difficult for new companies to enter due to high costs, technology, or patents.

- Mutual Interdependence: This is the most critical feature. It’s like a game of chess. Each company’s decision heavily depends on the actions and reactions of its rivals. Before changing its price, a company must think about how its competitors will react.

- Products: The products can be identical (like steel or cement) or differentiated (like cars or smartphones).

What is the result?

The behaviour of firms in an oligopoly can be complex. They might get into fierce price wars, which can be good for consumers. Or, they might try to avoid competition and engage in collusion—secretly agreeing to fix prices high. When they do this, they form a cartel, which is illegal and very harmful to consumers. This interdependence often leads to price rigidity, meaning prices don’t change very often.

- A special case of an oligopoly with only two firms is a Duopoly.

Examples in India:

- Telecommunications: Dominated by Jio, Airtel, and Vi.

- Automobile Industry: A few big players like Maruti Suzuki, Hyundai, Tata Motors, and Mahindra.

- Airlines, Cement, and Steel industries.

Why is this important for UPSC? (The CCI Connection)

These market structures are not just academic theories. They are the reason India has a law called the Competition Act of 2002 and a powerful regulator called the Competition Commission of India (CCI).

Think of the CCI as the referee of the market. Its job is to ensure fair competition, protect consumers, and stop companies from using unfair practices that come from these non-competitive market structures.

- When the CCI investigates cement companies for forming a cartel to fix high prices, it is directly tackling the problem of collusion in an oligopoly.

- When the CCI looks into a big e-commerce or tech company to see if it is abusing its powerful position, it is addressing the problem of abuse of dominance which is a feature of a monopoly.

So, understanding these market structures is essential to understand the work of the CCI and the logic behind India’s competition policies. The goal of the CCI is to push real-world markets to behave more like the efficient and consumer-friendly model of perfect competition.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Market Structures

| Feature | Perfect Competition | Monopolistic Competition | Oligopoly | Monopoly |

| Number of Firms | Very large | Many | Few | One |

| Type of Product | Homogeneous (Identical) | Differentiated | Homogeneous or Differentiated | Unique (No close substitutes) |

| Barriers to Entry | None / Very Low | Low | High | Very High / Blocked |

| Firm’s Control over Price | None (Price Taker) | Some | Considerable (Interdependent) | Significant (Price Maker) |

| Long-Run Profitability | Normal Profit Only | Normal Profit Only | Can be Supernormal Profit | Can be Supernormal Profit |

| Efficiency | High (Allocative & Productive) | Lower (Excess Capacity) | Varies (Often Inefficient) | Low (Allocative Inefficiency) |

| Real-World Indian Example | Agricultural Mandis, Stock Market | Restaurants, Clothing Brands | Telecom, Automobiles, Cement | Indian Railways (Operations) |

Part II: The Big Picture (Macroeconomics) and India

Section 5: Economic Systems and the Indian Model

First, what is an economic system? Think of it as a country’s “operating system.” It’s the set of rules and institutions that a country uses to answer the three big economic questions we discussed earlier:

- What to produce?

- How to produce it?

- For whom to produce it?

The economic system decides who owns the resources (like land and factories) and how they are used. Broadly, there are three main types of economic systems.

5.1 Capitalist (Market) Economy

In this system, the main player is the private individual or company. The government takes a backseat. Think of countries like the USA as examples.

What are its features? 💰

- Private Property: Individuals and private companies have the right to own property, like land, houses, and factories. It’s your personal asset.

- Profit Motive: The main reason for doing business is to earn a profit. This desire for profit is what drives innovation and production.

- Consumer Sovereignty: The consumer is the king. Companies will only produce what the consumers want to buy. If people start demanding more electric cars, companies will start producing more electric cars.

- Price Mechanism: Prices are not set by the government. They are decided freely in the market by the forces of demand and supply. These prices act as signals to producers about what to produce.

- Minimal Government Intervention: The government’s role is very limited. It acts like a referee—it protects people’s property rights and enforces contracts, but it doesn’t tell businesses what to do. This “hands-off” approach is called laissez-faire.

5.2 Socialist (Command) Economy

This system is the opposite of capitalism. Here, the main player is the government (the state). Think of the old Soviet Union or China in the past.

What are its features? 🏛️

- Public Ownership: The government owns and controls all the major resources and industries (factories, mines, banks) on behalf of the people. There is no private property in terms of production.

- Central Planning: Instead of the market, a central government authority (like a Planning Commission) makes all the economic decisions. It decides what will be produced, in what quantity, and who will get it.

- Social Welfare Objective: The main goal is not profit. The main goal is the welfare of the entire society and ensuring that wealth is distributed equally among all citizens.

- Absence of Competition: Since the state controls everything, there is little or no competition between different firms.

5.3 The Mixed Economy: The Middle Path

A mixed economy tries to take the good parts of both capitalism and socialism and put them together. It’s a middle path that tries to find a balance.

What is it? 🤝

A mixed economy is a system where both the private sector and the public (government) sector exist together and play important roles.

It tries to balance the efficiency and innovation of the market (from capitalism) with the goal of social welfare and equality (from socialism). The government allows people to own private property and run businesses, but it also steps in (intervenes) to regulate the economy, provide public services like education and healthcare, and help the poor.

Most countries in the world today, including India, the USA, and the UK, are mixed economies. The only difference is the “mix” – some have more capitalism, and some have more socialism.

5.4 The Indian Economy as a Mixed Economy: Our Journey

India has always been a mixed economy since 1947, but the “recipe” of our mix has changed dramatically over time.

Phase 1: After Independence (Before 1991) – The Government-led Model

After independence, India’s leaders were inspired by socialism. So, they chose a mixed economy where the government had the dominant role.

- Centralized Planning: India had a Planning Commission that created Five-Year Plans. These plans set goals for the economy and decided where resources should go.

- Dominant Public Sector: The government set up many Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) and took control of the most important industries like steel, banking, and mining. These were called the “commanding heights” of the economy.

- Heavy Regulation (The “Licence Raj”): The private sector was heavily controlled. You needed a government license or permit for almost everything—to start a factory, to expand production, or to import goods. Our economy was also closed off from the rest of the world to protect our domestic industries (protectionism). This system led to slow growth, inefficiency, and a lot of corruption.

Phase 2: After 1991 – The Shift towards the Market

By 1991, India was facing a huge economic crisis. To solve this, the government introduced the famous LPG Reforms (Liberalisation, Privatisation, Globalisation). This was a massive turning point. India began to shift its “mix” away from socialism and more towards a market-oriented (capitalist) system.

- The “Licence Raj” was dismantled.

- The role of the public sector was reduced, and many areas were opened up for private companies.

- The economy was opened to foreign trade and investment.

How India’s Mixed Economy Looks Today 🇮🇳

Today, India’s mixed economy has the following features:

- Coexistence of Public and Private Sectors: We have government-owned companies in key areas like Defence and Railways. But the private sector is now the main engine of our economic growth, leading in areas like IT, services, and manufacturing.

- Changed Role of Planning: The old Planning Commission has been replaced by NITI Aayog. NITI Aayog is not a central planner; it acts more like a “think tank” or an advisor to the government.

- Balance of Freedom and Control: Private companies have a lot of freedom. But the government still regulates important sectors like banking and telecom. It also provides a social safety net for the poor through schemes like the PDS (ration shops) and MGNREGA (job guarantee scheme).

- Focus on Citizen Welfare: The goal of social welfare is still very strong. We see this in the government’s many schemes for the poor, like Ayushman Bharat (health insurance), PMAY (housing for all), and PM-KISAN (income support for farmers).

Why this is SUPER IMPORTANT for UPSC

This evolution of India’s mixed economy is the key to understanding almost every major economic debate today. When you read about issues like:

- The government selling its stake in PSUs (disinvestment)

- The new laws for agricultural markets

- The new labour codes

…all these are fundamentally debates about the right “mix” between the government (state) and the private sector (market).

When writing a UPSC Mains answer, a top-quality response must analyse this tension.

- Example: Disinvestment of a PSU.

- The pro-market argument: It will bring efficiency, competition, and unlock capital.

- The pro-state/welfare argument: It could lead to job losses, harm social equity, and give up control of a strategic national asset.

Your answer should show that you understand these trade-offs between the goal of economic efficiency and the goal of social welfare.

Section 6: Measuring the Economy: National Income Accounting

Think of National Income Accounting as the government’s system of bookkeeping. It’s like creating a “report card” for the entire country’s economy to see how well it’s performing. This is done every year or every quarter (three months).

This report card is very important for the government to make plans and policies. The most famous number on this report card is the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

6.1 Core Concepts of National Income

Let’s understand the most important terms one by one.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 🇮🇳 This is the big one you hear about in the news all the time.

- Definition: GDP is the total money value of all final goods and services produced within the domestic territory of a country in a specific time period.

- What does “final” mean? It means we only count the value of the finished product, not the parts that went into making it. This is to avoid double-counting.

- Example: To make a car (final good), you need tyres, steel, and glass (intermediate goods). If the final car is sold for ₹5 lakhs, we just count ₹5 lakhs. We don’t separately add the value of the tyres (say, ₹20,000) because their cost is already included in the car’s price. If we did, we would be counting the tyres’ value twice!

- What does “within the domestic territory” mean? It means it’s about geography. Anything produced within India’s borders is counted in India’s GDP, no matter who owns the company.

- Example: A car made by a Korean company like Hyundai in its factory in Chennai is a part of India’s GDP. However, the profit earned by an Indian company like Tata Motors in its factory in the UK is not part of India’s GDP.

Gross National Product (GNP) 👩💼 This is slightly different from GDP. It’s about who is producing, not where they are producing.

- Definition: GNP is the total money value of all final goods and services produced by the nationals (citizens) of a country, regardless of where they are in the world.

- The formula to connect them is: GNP = GDP + NFIA

- What is NFIA? It stands for Net Factor Income from Abroad. In simple terms:

- NFIA = (Money earned by Indians working abroad) – (Money earned by foreigners working in India).

- For India: Historically, the money earned by foreigners working in India has been more than the money earned by Indians working abroad. So, India’s NFIA is negative. This means for India, GNP is usually lower than its GDP.

Net Domestic Product (NDP) and Net National Product (NNP) 🔧 The words “Gross” in GDP and GNP mean we haven’t accounted for something called depreciation.

- What is Depreciation? It’s the natural wear and tear of capital goods like machines, buildings, and roads over time. A machine in a factory gets old and loses value every year. This loss in value is depreciation.

- The word “Net” simply means after subtracting depreciation.

- NDP = GDP – Depreciation

- NNP = GNP – Depreciation

- “Net” figures are considered a more accurate measure of a country’s real income because they show what’s left after accounting for the maintenance of our assets.

- Very Important Point: The NNP at Factor Cost is generally what is called the National Income of a country.

6.2 Factor Cost vs. Market Price

The value of a product can be looked at in two ways:

- Market Price (MP): This is the actual price you and I pay for a product in a shop. This price includes indirect taxes (like GST) that the government adds, and it is reduced by any subsidies the government gives.

- Example: If a bottle of soft drink costs ₹18 from the factory, the government might add ₹2 as GST. So, the market price you pay is ₹20.

- Factor Cost (FC): This is the price of the product from the producer’s point of view. It is the cost of all the “factors of production” used to make it (rent for land, wages for labour, profit for the entrepreneur). It does not include the tax paid to the government. In the above example, the factor cost is ₹18.

The relationship is: Market Price = Factor Cost + Indirect Taxes – Subsidies

6.3 Real vs. Nominal GDP

This is a very important concept to understand true economic growth.

- Nominal GDP: This is the GDP calculated using the prices of the current year. Nominal GDP can go up for two reasons: (1) we actually produced more goods and services, OR (2) the prices of everything went up (inflation). So, it can be misleading.

- Real GDP: This is the GDP calculated using the prices of a fixed base year. By keeping the prices constant, Real GDP removes the effect of inflation and shows us only the change in the actual quantity of goods and services produced.

Real GDP is the true measure of a country’s economic growth.

- Example:

- In 2020 (base year), India makes 10 cars at ₹5 lakh each. GDP = ₹50 lakh.

- In 2025, India makes 11 cars, but the price is now ₹6 lakh each.

- Nominal GDP for 2025 = 11 cars × ₹6 lakh = ₹66 lakh.

- Real GDP for 2025 (using 2020 prices) = 11 cars × ₹5 lakh = ₹55 lakh.

- The real economy grew from ₹50 lakh to ₹55 lakh. The rest of the increase in the Nominal GDP was just due to price rise (inflation).

GDP Deflator: This is a tool to measure the overall inflation in the economy.

- Formula: GDP Deflator = (Nominal GDP / Real GDP) × 100

6.4 Methods of Calculation in India

There are three ways to calculate a country’s national income. In theory, all three should give the same result.

- Production (Value Added) Method: Here, we add up the Gross Value Added (GVA) from all three sectors of the economy:

- Primary Sector (Agriculture)

- Secondary Sector (Industry/Manufacturing)

- Tertiary Sector (Services)

- (GVA is the value of the final product minus the cost of inputs used to make it).

- Income Method: Here, we add up all the incomes earned by people in the country. This includes:

- Wages and salaries of employees.

- Rent, interest, and profits earned by owners of capital.

- Mixed income of self-employed people (like doctors, shopkeepers).

- Expenditure Method: Here, we add up all the spending done in the economy on final goods and services. The formula is:

- GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

- C = Private Consumption (spending by households like us).

- I = Investment (spending by businesses on new factories, machines).

- G = Government Spending (on roads, salaries, defence).

- (X – M) = Net Exports (Value of Exports minus Value of Imports).

6.5 Recent Changes in India’s GDP Calculation (Post-2015)

This is a very important topic for the UPSC exam. In 2015, the way India calculates its GDP was changed significantly.

What were the key changes?

- New Base Year: The base year for calculating Real GDP was updated from 2004-05 to 2011-12. This is done periodically to make sure the GDP calculation reflects the modern economy.

- Shift to Market Price: The main GDP figure is now reported at Market Prices, not Factor Cost. This is the international standard.

- Use of GVA: For sector-wise breakdown, the term Gross Value Added (GVA) at basic prices is now used.

- Bigger Data Source (MCA-21): This was the biggest change. Earlier, the data was taken from a survey of about 2 lakh companies. Now, the government uses the official financial data filed by over 5 lakh companies with the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (this database is called MCA-21). This gives a much wider and more formal view of the corporate sector.

- Better Coverage: Data from other sectors like finance and local governments was also improved.

The Debate and Challenges After the Change

These changes were made to improve the quality of data and follow global standards. However, they also led to a big debate.

- It became difficult to compare the economic growth before and after 2015.

- For a few years after the change, the new GDP numbers showed strong growth, but other indicators like factory production and job creation were weak. This made many economists question the reliability of the new numbers.

- “Discrepancies”: In the final data, there is often a difference between the GDP calculated by the production method and the expenditure method. This difference is called a “discrepancy.” A large discrepancy suggests that there are problems in collecting data, especially from India’s huge informal sector (small shops, daily wage labourers etc.), which is very hard to measure accurately. This is a major challenge for Indian policymakers.

Section 7: Inflation and Price Stability

Inflation is one of the most important macroeconomic topics. It directly impacts the life of a common person (our well-being), the profits of businesses, and the health of the entire economy. For any government in India, controlling inflation is a top priority.

7.1 Understanding Inflation

What is Inflation? 🤔

In the simplest words, inflation is the rate at which the prices of most goods and services are increasing over time. It is also known as mehengai.

This means that the purchasing power of your money goes down. The ₹100 note in your pocket can buy fewer things today than it could last year.

Important points to remember:

- The price rise must be sustained, meaning it should continue for a period of time. A sudden one-day jump in the price of tomatoes is not inflation.

- The price rise must be general, meaning the prices of most things in the economy (food, clothes, fuel, services) are rising, not just one or two items.

The opposite of inflation is deflation, which is when the prices of most things are continuously falling.

7.2 Types and Causes of Inflation

Inflation can happen for different reasons. Let’s look at the main causes.

- Demand-Pull Inflation

This is the most common type. The classic way to describe it is: “Too much money chasing too few goods.”

This happens when the total demand for goods in the country is much higher than the total supply. Everyone wants to buy things, but there aren’t enough things to go around. This excess demand “pulls” the prices up.

- What causes this high demand?

- More money in the economy: If the RBI prints a lot of money, or if banks give out a lot of cheap loans, people have more money to spend.

- Government spending: If the government spends a lot on new projects or cuts taxes, people are left with more money in their hands.

- Rising Incomes: If people get good salary hikes and feel confident about the future, they tend to spend more.

- Black Money: A lot of hidden, untaxed money can also create extra demand.

- Cost-Push Inflation

This type of inflation comes from the producer’s side. It happens when the cost of making a product goes up. To protect their profits, companies are forced to increase the selling price of the final product. The rising cost is “pushing” the price up.

- What causes these costs to go up?

- Rise in Raw Material Prices: A big jump in the global price of crude oil is a classic example. When oil becomes expensive, petrol and diesel prices go up. This increases the transportation cost for everything, from vegetables to cars, making them all more expensive.

- Higher Wages: If companies have to pay higher salaries to their workers without the workers becoming more productive, their costs increase.

- Infrastructure Problems: Bad roads, crowded ports, or lack of warehouses can increase the cost of transportation and logistics for businesses.

- Higher Taxes: If the government increases indirect taxes like GST, the final price of the product for the consumer goes up.

- Structural Inflation

This is a special kind of inflation that is very common in developing countries like India. It is caused by long-term weaknesses or “structural problems” in the economy, especially in the agriculture sector.

Think of it like trying to fill a bucket that has holes. No matter how much water you pour, the structural problems (the holes) cause wastage and problems.

- What are these structural problems in India?

- Inefficient Supply Chains: A large portion of fruits and vegetables get wasted before they can even reach the market from the farms.

- Lack of Storage: We don’t have enough cold storage facilities, so when there is a bumper crop of onions or potatoes, we can’t store them properly, leading to shortages later.

- Market Imperfections: Sometimes, big traders hoard essential goods (like pulses) to create an artificial shortage and then sell them at a very high price. This is illegal.

7.3 How We Measure Inflation in India

We can’t track the price of every single item. So, we measure inflation using a price index.

A price index is simple. The government creates a “shopping basket” of goods and services that a typical family consumes. Then, it tracks the total cost of this basket every month. The percentage change in the cost of this basket is the inflation rate.

In India, we use two main price indices:

- Wholesale Price Index (WPI)

- What it measures: It tracks the prices of goods at the wholesale level. This is the price at which factories sell to wholesalers, or wholesalers sell to retailers (in bulk). It measures inflation from the producer’s point of view.

- Who publishes it: Office of the Economic Adviser, Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

- What’s in its basket:

- Only Goods, no services.

- The highest weightage is given to Manufactured Products (like steel, chemicals, textiles), which make up about 64% of the basket.

- Limitations:

- It does not include services like education, healthcare, or transport, which are a big part of our expenses.

- It does not show the price that we, the final consumers, actually pay in the shops.

- Consumer Price Index (CPI)

- What it measures: This tracks the prices of goods and services at the retail level. This is the price that you and I, the consumers, pay. It is the best measure of the cost of living.

- Who publishes it: The main CPI data is released by the National Statistical Office (NSO).

- What’s in its basket:

- It includes both Goods and Services.

- A very important difference from WPI: The highest weightage is given to Food and Beverages, which makes up about 45% of the basket. This is because an average Indian family spends a large part of its income on food.

- Policy Relevance (Very Important!): The CPI is the main inflation measure used by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to make its policy decisions. When the RBI decides to increase or decrease interest rates, it is looking at the CPI number. The government has given the RBI a target to keep CPI inflation around 4%.

Table 2: WPI vs. CPI – A Detailed Comparison for UPSC

| Parameter | Wholesale Price Index (WPI) | Consumer Price Index (CPI – Combined) |

| Stage of Transaction | Wholesale level (Producer/Trader) | Retail level (Final Consumer) |

| Publishing Agency | Office of Economic Adviser (Ministry of Commerce) | National Statistical Office (NSO) |

| Base Year | 2011-12 | 2012 |

| Goods/Services Covered | Goods only | Both Goods and Services |

| Major Component (Highest Weightage) | Manufactured Products (~64%) | Food and Beverages (~45%) |

| Use in Policy Making | Used as a key indicator of producer-side inflation | Official target for RBI’s Monetary Policy |

| Reflection of Consumer Burden | Indirectly reflects costs passed on to consumers | Directly measures the cost of living for households |

7.4 How India Fights Inflation: The Policy and the Plan

The way India tries to control inflation has changed a lot in recent years. It has become much more modern and systematic.

- The Big Shift: From WPI to CPI Targeting 🎯

- The Old Way: For many years, the RBI used the WPI (Wholesale Price Index) as its main guide to check inflation. The problem was, as we discussed, WPI measures prices at the wholesale level and doesn’t include services. It was not an accurate measure of the actual cost of living for a common person.

- The Change: A committee headed by the former RBI Governor, Dr. Urjit Patel, recommended that the RBI should stop using WPI and start using CPI (Consumer Price Index).

- The New Way: In 2014, the RBI officially adopted this recommendation. The CPI became the new main measure of inflation for all its policy decisions. This was a major step because CPI accurately reflects the prices that you and I, the consumers, actually pay.

- The New System: Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) and the MPC

In 2016, the system was made even better by making a change in the RBI Act (the law that governs the RBI). This created a modern framework for fighting inflation.

- The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) was created:

- This is a powerful six-member committee. Three members are from the RBI (including the Governor), and three members are appointed by the government.

- The main job of the MPC is to decide the policy repo rate. The repo rate is the interest rate at which the RBI lends money to other banks. This is the most powerful tool to control the money supply and inflation in the economy.

- A New Strategy called Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) was introduced:

- This means the government and the RBI have officially set a specific target for inflation.

- The Target: The target for CPI inflation is 4%.

- The “Flexible” Part: The target is not rigid. There is a “tolerance band” or a safe range of +/- 2 percent.

- This means the RBI’s official, legal mandate is to keep the CPI inflation within the range of 2 percent to 6 percent.

Think of it like setting the thermostat of an air conditioner. You set the ideal temperature to 24 degrees (the 4% target), but you are comfortable as long as it stays between 22 and 26 degrees (the 2% to 6% band). The MPC’s job is to keep the economy’s “temperature” within this comfortable band.

Why was this change so important for India?

This new system completely changed the way the RBI works. It was a fundamental shift in its philosophy.

- Before (The Old Way): The RBI had many goals to juggle at the same time. It had to control inflation, but also push for economic growth, and also keep the rupee stable. There was no clear number one priority. It was a difficult balancing act.

- Now (The New Way): The RBI has one primary, legally-mandated goal: Price Stability (which means keeping inflation within the target). All other goals, like growth, are now secondary to this main goal. This has made the RBI’s job much clearer and more focused.

Benefits of the New System:

- More Credibility and Accountability: The RBI is now more trustworthy and accountable. Everyone knows exactly what its main job is, and we can judge its performance based on a clear number.

- Clear Performance Report Card: We can easily see if the MPC is doing its job. Is inflation between 2% and 6%? If yes, they are succeeding. If it goes above 6% or below 2%, they are failing.

- Punishment for Failure: There is a clear rule. If inflation stays outside the 2% to 6% band for three consecutive quarters (which is 9 months), the RBI is legally required to write a report to the government. In this report, it must explain:

- Why it failed to meet the target.

- What steps it will take to bring inflation back into the target range.

- Controls People’s Expectations: Because the system is so transparent and rule-based, it helps control what people and businesses expect about future inflation. When people believe that the RBI is serious about controlling prices, they act accordingly, which itself helps to keep inflation low.

Section 8: Employment and Unemployment

The job situation in a country is like its health report. If many people have jobs, the economy is healthy. If many are unemployed, the economy is sick. For a huge country like India, creating jobs and solving the problem of unemployment (having no job) and underemployment (having a job but not getting enough work or pay) is a top priority for the government.

8.1 Key Numbers to Measure the Job Market

To understand the employment situation, we use a few key indicators. The data for these mostly comes from a big government survey called the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS).

- Labour Force: This is the total number of people who are available to work. It includes two groups of people:

- Employed: People who are currently working.

- Unemployed: People who are not working but are actively searching for a job or are available to work.

-

- Who is NOT in the Labour Force? People who are neither working nor looking for work are considered out of the labour force. This includes students, full-time homemakers, and retired pensioners.

- Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR): This tells us what percentage of the total working-age population is part of the labour force. A high LFPR is good; it means more people are actively working or wanting to work.

- Worker Population Ratio (WPR): This tells us what percentage of the total working-age population actually has a job.

- Unemployment Rate (UR): This is the most famous number. It tells us the percentage of people in the labour force who do not have a job.

- Formula: Unemployment Rate = (Total Number of Unemployed People / Total Labour Force) × 100

- Important: It’s a percentage of the labour force, not the total population.

8.2 Types of Unemployment in India

Unemployment in India is a complex problem. Here are the different types you will find:

- Structural Unemployment: This is India’s biggest and most serious type of unemployment. It’s a skills mismatch. There are jobs available, and there are people looking for jobs, but the skills of the people don’t match the skills required for the jobs.

- Example: An IT company in Bengaluru needs 100 software engineers with AI skills, but the people applying for the job have only a basic BA degree. This is a long-term problem caused by issues in our education and training systems.

- Disguised Unemployment: This means “hidden” unemployment. It happens when more people are working on a job than are actually needed.

- Example: A small family farm can be managed by 2 people. But in the family, there are 5 members, and all of them work on that same farm. The extra 3 people are not adding anything to the total production. If they leave the farm, the output will remain the same. These 3 people are in disguised unemployment. This is very common in Indian agriculture.

- Seasonal Unemployment: This happens when people get work only during certain seasons of the year.

- Example: A farm labourer gets a lot of work during the sowing and harvesting seasons but may be unemployed for the rest of the year. Similarly, an ice cream seller has good business in summer but very little in winter.

- Frictional Unemployment: This is temporary, “in-between jobs” unemployment. It happens when a person leaves their old job and is in the process of joining a new one. This is a normal part of any healthy economy and is not a major concern.

- Cyclical Unemployment: This is caused by the ups and downs of the economy (the business cycle). When the whole economy goes into a recession (a slowdown), companies reduce production and fire workers. This is a bigger problem in developed countries.

- Technological Unemployment: This is when people lose their jobs because of new technology like automation, robots, or Artificial Intelligence (AI).

- Example: The job of a bank cashier being replaced by an ATM or cash deposit machine.

8.3 How Unemployment is Measured in India

Measuring unemployment in India is very difficult. This is because a large part of our economy is the informal sector, where jobs are often temporary and not officially recorded. A daily wage labourer might have work for three days, be unemployed for four days, and it’s hard to classify them.

To handle this complexity, the National Statistical Office (NSO) uses three different methods, which are like three different lenses to look at the same problem. They differ based on the reference period (the time period they look at).

The Three Methods:

- Usual Status (US): This method looks at a long reference period of the last 365 days. It is used to measure long-term or chronic unemployment. It asks, “What was your main employment status over the last year?”

- Current Weekly Status (CWS): This method looks at a short reference period of the last 7 days. A person is considered employed if they worked for even one hour on at least one day during that week. This is better for measuring short-term unemployment.

- Current Daily Status (CDS): This is the most detailed and sensitive measure. It looks at each day of the last 7 days. It measures work in “person-days.” If a person worked for only half a day, they are counted as 0.5 person-days employed and 0.5 person-days unemployed. The CDS is the best measure to capture underemployment—the problem of not having enough work.

The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS)

To get more regular and timely data, the government started the PLFS in 2017. Before this, such detailed surveys were done only once every five years. The PLFS provides job data every quarter for urban areas and every year for the whole country.

Why are there different numbers? The UPSC Mains Angle.

This is the most important part for your analysis. The unemployment rate calculated by these three methods is always different.

- The rate as per Usual Status is the lowest.

- The rate as per CWS is in the middle.

- The rate as per CDS is the highest.

What does this tell us? It tells a very important story about the Indian job market. While the long-term unemployment rate (Usual Status) might look low, the much higher CDS rate reveals the true and biggest challenge for India: underemployment and poor-quality, unstable jobs.

- Example: A casual construction worker gets work for only 3 days in a week.

- According to the CWS method, he is considered “employed” because he worked for at least one hour in the week. The data would show him as employed.

- However, the CDS method would accurately show that he was unemployed for 4 out of the 7 days of the week. This gives a much more realistic picture of his hardship.

Key takeaway for your UPSC answer: A simple answer will just state the low Usual Status unemployment rate. A nuanced, high-scoring answer will highlight the difference between the three rates. It will argue that India’s main policy focus should not just be on creating any job, but on creating good quality, stable, and full-time jobs to solve the deep problem of underemployment, which is best captured by the CDS measure.

Part III: Development, Welfare, and the Economy’s Ups and Downs

Section 9: Poverty and Inequality

Poverty (garibi) and inequality (asamanata) are two of the biggest challenges in India’s development story.

It’s important to know that just because the economy is growing (our national income or GDP is increasing), it doesn’t automatically mean poverty will disappear. Economic growth is necessary, but it’s not enough. How that growth happens and who gets the benefits are just as important.

Think of it like this: Baking a bigger cake (economic growth) is good. But if only a few people get all the big slices while many get tiny crumbs, then the problem of hunger (poverty) and unfairness (inequality) remains.

9.1 How We Define and Measure Poverty: The Poverty Line

What is Poverty? Poverty is a situation where a person or a family doesn’t have enough money or essential resources to live a basic, minimum standard of life.

The Poverty Line To measure poverty, India has traditionally used the concept of a “poverty line.”

- Think of it as a minimum “passing mark.” It’s an imaginary line that sets a threshold for monthly spending (consumption expenditure).

- If a person’s monthly spending is below this line, they are classified as Below the Poverty Line (BPL).

How the Idea of the Poverty Line Changed Over Time

- The Old Way (based on calories): In the beginning, the poverty line was very basic. It was calculated based on the minimum calories a person needs just to survive (e.g., 2400 calories per day in villages and 2100 in cities, as suggested by the Alagh Committee in 1979).

- The Problem with the Old Way: This approach was heavily criticised. It was seen as just a “starvation line”. It only cared about food and completely ignored other essential things a person needs for a decent life, like clothing, a house, healthcare, and education.

9.2 Estimating Poverty in India: The Main Committees

The method to calculate the poverty line has been updated over the years by different expert committees. For the UPSC exam, two committees are very important: Tendulkar and Rangarajan.

- Tendulkar Committee (2009)

This committee changed the way we looked at poverty in a big way.

- What they did differently (Methodology):

- They moved away from the old calorie-only method.

- They created a “Poverty Line Basket” of goods and services. This basket included not just food, but also what people were actually spending on health and education. This made the poverty line much more realistic.

- What was the Poverty Line? (for 2011-12):

- For rural areas: ₹816 per person per month (which is about ₹27 per day).

- For urban areas: ₹1,000 per person per month (which is about ₹33 per day).

- How many people were poor? (Poverty Estimate):

- Based on this line, the committee estimated that 21.9% of India’s population was below the poverty line in 2011-12.

- Status (Very Important!): The Tendulkar Committee’s estimates are the last officially accepted poverty figures for India.

- Rangarajan Committee (2014)

This committee was set up to review the Tendulkar methodology.

- What they did differently (Methodology):

- They suggested a higher and more generous poverty line.

- They went back to creating separate consumption baskets for rural and urban areas.

- Their food basket was based on ideal norms for calories, proteins, and fats. They also included higher amounts for essential non-food items like clothing and rent.

- What was the Poverty Line? (for 2011-12):

- For rural areas: ₹972 per person per month (about ₹32 per day).

- For urban areas: ₹1,407 per person per month (about ₹47 per day).

- How many people were poor? (Poverty Estimate):

- Because their poverty line was higher, they estimated that a much larger portion of the population, 29.5%, was poor in 2011-12.

- Status (Very Important!): The government did not officially adopt or accept the recommendations of the Rangarajan Committee.

What is the situation now? (Contemporary Context)

This is a major challenge and a hot topic for discussion.

- We do not have any official poverty estimates after 2011-12. This is a big “data vacuum.”

- Because of this, other ways of measuring poverty have become more important:

- The World Bank’s International Poverty Line: The World Bank uses a global standard (like an income of less than $2.15 per day) to compare poverty across different countries.

- NITI Aayog’s Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI): This is the new, modern approach that India is now focusing on. It’s “multidimensional” because it looks beyond just money. It measures poverty based on deprivations in three key dimensions:

- Health (e.g., nutrition, child mortality).

- Education (e.g., years of schooling).

- Standard of Living (e.g., access to clean cooking fuel, sanitation, drinking water, electricity). This gives a much more complete and useful picture of poverty.

Table 3: Tendulkar vs. Rangarajan Committee – A Methodological Comparison

| Parameter | Tendulkar Committee (2009) | Rangarajan Committee (2014) |

| Consumption Basket | Uniform All-India Urban basket used as reference for both rural and urban areas. | Separate consumption baskets for rural and urban areas. |

| Basis for Food Expenditure | Based on observed consumption patterns. | Based on normative satisfaction of calorie, protein, and fat requirements. |

| Inclusion of Non-Food Items | Included observed private expenditure on health and education. | Included higher normative expenditure on essential non-food items. |

| Poverty Line (2011-12) | Rural: ₹816/month; Urban: ₹1,000/month | Rural: ₹972/month; Urban: ₹1,407/month |

| National Poverty Ratio (2011-12) | 21.9% | 29.5% |

| Official Acceptance Status | Accepted by the then Planning Commission. | Not officially adopted by the government. |

9.3 How We Measure Inequality

First, let’s be clear about the difference between poverty and inequality.

- Poverty is about people not having enough money to live a basic life.

- Inequality is about the gap between the rich and the poor. It measures how the country’s total income is shared among its people.

A country can have very few poor people, but still have very high inequality if a few super-rich people have most of the money, while the rest of the population has just enough to get by.

To measure this gap, we use two main tools:

- The Lorenz Curve

This is a graph (a picture) that shows us the level of inequality.

- Imagine a square box. We draw a straight, diagonal line from the bottom-left corner to the top-right corner. This line is called the Line of Perfect Equality. It represents a perfectly equal world where the bottom 10% of people have 10% of the total income, the bottom 50% of people have 50% of the income, and so on.

- Then, we plot the actual data for a country. This creates a curved line below the straight line. This curved line is the Lorenz Curve.

- The main idea is simple: The bigger the gap between the straight line (perfect equality) and the curved line (the reality), the more inequality there is in the country. If the curve is very far away and bowed down, it means inequality is very high.

- The Gini Coefficient

The Gini Coefficient is a number or a score that is calculated from the Lorenz Curve. It gives us a single, easy-to-understand measure of inequality.

- This score ranges from 0 to 1 (or 0 to 100).

- What the score means:

- A score of 0 means Perfect Equality (everyone has the exact same income).